The SL-1 Accident: The First Fatal Nuclear Energy Explosion

It’s still the deadliest nuclear accident in American history, but not many people are familiar with the story. I didn’t learn about it until I was an adult—and the town I grew up in was only 40 miles away from where the accident took place. So what went wrong with the SL-1 nuclear reactor? If you’re curious, you can dig into the maps and information below. And if you want to know even more, check out the Wild Thing nuclear podcast for a deeper look into SL-1 and our history with nuclear energy.

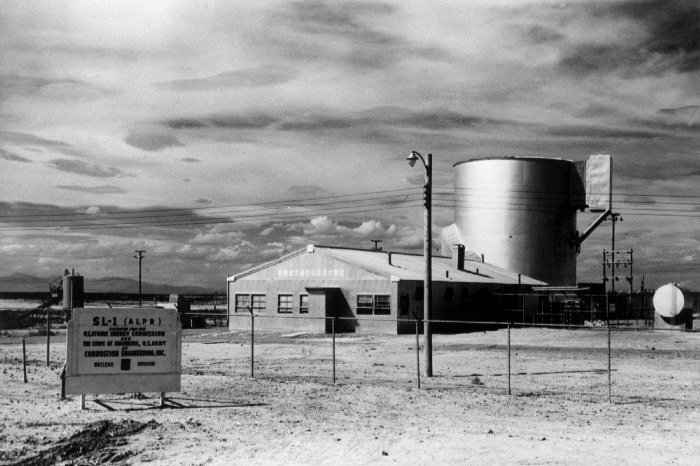

SL-1 Nuclear Power Reactor / US Army

What is SL-1?

Schematic of a Boiling Water Reactor / US Nuclear Regulatory Agency

SL-1 (which stands for Stationary Low-Power Reactor Number One) was an experimental type of nuclear reactor known as a boiling water reactor. In this type of reactor, water flows into the reactor vessel, which is the part of the reactor that holds the fuel. As the atoms inside the fuel fission, the heat from that process causes the water to boil, creating steam. The steam then turns a turbine, creating electricity.

SL-1 was built and began producing power in October 1958. It had been designed to generate about 200 kilowatts of electricity—about enough to power one radar station.

SL-1 Location

SL-1 was located in the Arco Desert of eastern Idaho at what was then the National Reactor Testing Station (NRTS) and is now the Idaho National Laboratory (INL). Established in 1949, the NRTS was essentially a giant laboratory where scientists and the military could experiment with nuclear energy.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Navy developed and built the prototype for the first ever nuclear submarine, the USS Nautilus. The Air Force attempted to make a nuclear powered airplane—a project that, ahem, never got off the ground. And the Army wanted to create smaller, self-contained nuclear plants that could power far-flung military bases and eliminate the expensive and dangerous process of refueling them. SL-1 was a prototype for this sort of reactor.

The SL-1 Accident

Burial Grounds of SL-1 reactor / John R. Giles, EPA

On January 3, 1961 at 9:01pm, one of the three crewmen working at SL-1 manually pulled up the central control rod of the reactor as part of a routine maintenance procedure. The rod was withdrawn too far and the reactor went super critical, instantaneously driving the temperature inside the reactor up to 2,000 degrees Celsius. That intense heat caused much of the water inside the reactor’s core to flash into steam, creating so much pressure that it launched the reactor tank into the air and expelled reactor parts and debris.

One crewman, Dick Legg, was impaled by a control rod that pinned him to the ceiling of the SL-1 building. A second, Jack Byrnes, was directly killed by the explosion of steam. The third, Richard McKinley, survived the initial blast only to die a few hours later from his injuries. The SL-1 accident remains the only fatal nuclear reactor accident in the U.S.

The SL-1 Love Triangle

Composite image of Richard McKinley, Jack Byrnes, and Dick Legg

To this day, it isn’t entirely clear why one of the crewmen withdrew the central control rod so far that it caused the chain reaction that led to the explosion. Almost everyone I interviewed and everything I read suggested that the condition of the reactor was responsible for the accident—there had been multiple reports of poor maintenance and design flaws.

However, one of the rumors that circulated after the explosion intimated that a love triangle was to blame. The story suggested that one crewman had started sleeping with the wife of another crewman and the injured party deliberately withdrew the control rod in a murder-suicide that destroyed the reactor and killed everyone inside.

Despite a complete lack of evidence, this salacious piece of gossip has persisted for decades and even made its way into government reports about the accident. It may have provided a convenient way to shift people’s attention from the problems with the reactor itself.

The SL-1 Cleanup

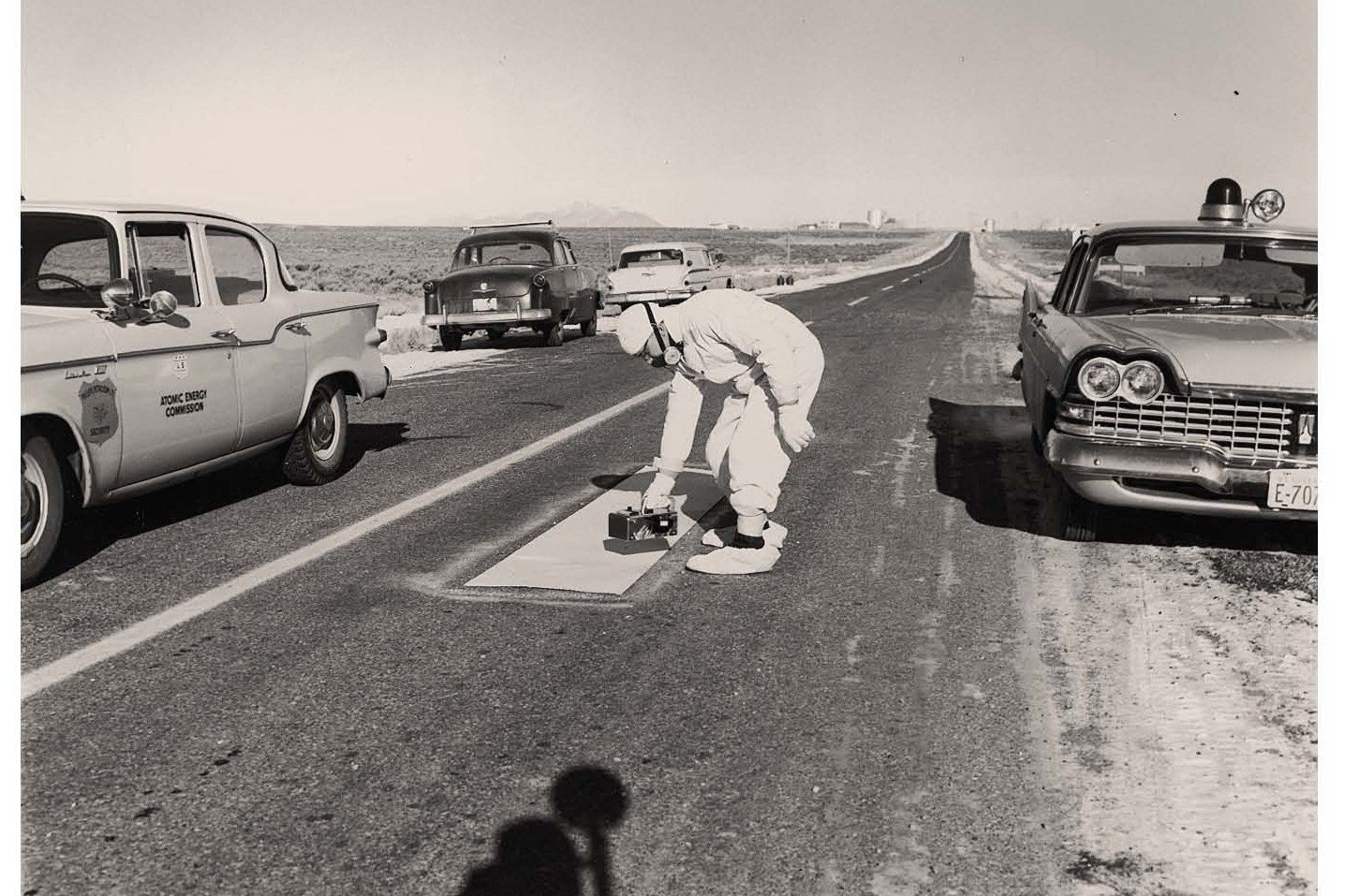

Health Physicists check Highway 20 for contamination on the morning after the SL-1 accident. / INL

Immediately after the accident, the first step involved recovering the injured Richard McKinley (who would die shortly after rescue), and then the bodies of the two other men. It took 24 hours to retrieve Jack Bynes’s body and a full six days to extract Dick Legg, who had been pinned to the ceiling.

All three men’s bodies had been exposed to incredibly high levels of radiation, making them dangerously radioactive. After a gruesome autopsy (the details of which you can read about in Todd Tucker’s excellent book Atomic America), the men were buried in lead-lined caskets and their funerals kept short to avoid exposing mourners. As an added precaution, the military lined Dick Legg’s grave with three feet of concrete.

Then there was the problem of the reactor itself. What remained of the SL-1 reactor had to be dismantled by workers who were only allowed to work a few minutes at a time because of the high levels of radioactivity. Some materials were buried; others hauled away. The adjacent building was left in place and people continued to work there until the 1980s, when there was a better understanding of just how high the radiation levels still were. At that point, the entire structure was finally demolished. The site has been decontaminated and tested multiple times to ensure the radiation is and remains contained.

For more on SL-1, the accident, and our history with nuclear energy, check out Wild Thing: Going Nuclear.

Laura Krantz is the host and producer of the Wild Thing podcast, which explores the relationship between science and society.